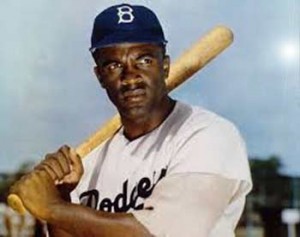

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson, wearing his brand-new Brooklyn Dodgers uniform, walked onto Ebbets Field and changed the face of baseball forever. As the first African-American ballplayer signed to a major league team, he was breaking a color barrier that had existed for many decades.

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson, wearing his brand-new Brooklyn Dodgers uniform, walked onto Ebbets Field and changed the face of baseball forever. As the first African-American ballplayer signed to a major league team, he was breaking a color barrier that had existed for many decades.

From the start, Jack Roosevelt Robinson was subjected to unrelenting hostility from both fans and teammates. But he honored the contract he had signed with manager Branch Rickey and ignored it all. After a dazzling first season, he was named Rookie of the Year and for, the next decade, he enjoyed a stellar career while waging a continual battle against racism.

Right beside him all the way was his wife, Rachel, the love of his life, who raised their three children in the hot glare of publicity and during some of the most turbulent years of the Civil Rights Movement. The Robinsons persevered, Rachel says now, because they understood the symbolic importance of Jack’s career: “We believed enough in each other and what we were doing to transcend the immediate.”

As the fiftieth anniversary of that first, momentous game approaches, Rachel, now 73, has written a book, Jackie Robinson, An Intimate Portrait, which tells the private side of the couple’s triumphs and ordeals during their 32 years together.

They met in the fall of 1940 as students at the University of California, Los Angeles and became engqged the next year. Jack went on to serve in the army and was court-martialed for refusing to ride at the back of a military bus. After playing in the Negro Leagues, he signed with the Dodgers in 1945.

Rachel and Jack married in a church ceremony in Los Angeles in February 1946. Two weeks later, they traveled to Daytona Beach, FL, for the Dodgers’ minor-league Triple A spring training. They lived in separate quarters from the rest of the team because hotels refused to give them a room. All restaurants in town were closed to blacks as well. At the ballpark, fans threw beer cans.

Even after the Robinsons settled in Brooklyn, they faced challenges. Three of Jack’s teammates tried to petition management to get him off the team. And there were deliberate efforts to physically hurt him. Rachel writes that players slid into the base Jack was covering with spikes high, trying to draw blood; pitchers threw balls at his head intending to injure him. Off the field, there were death threats. To get through it, “we cried, laughed, made fun of people,” she says. And they grew closer.

Rachel felt she couldn’t afford to miss a home game. “I felt I needed to be there to share in what was happening to Jack,” she writes. “I sat through name-calling, jeers, and vicious baiting in a furious silence. My only response was to sit up very straight, as if my back could absorb the outbursts and prevent them from reaching him.”

In 1957, Jack retired from baseball. Rachel had enjoyed being a homemaker, but now wanted “to develop myself and be a person in my own right.” In 1960, she earned a master’s degree in psychiatric nursing from New York University. Later, she would help create and operate the first U.S. day-hospital for acutely ill psychiatric patients and teach nursing at Yale University Medical School. Meanwhile, Jack moved on to a successful business career and a leadership position in the Civil Rights Movement. But the Robinsons paid a high price for blazing a new path.

Their biggest personal tragedy was the loss of their eldest son, Jack, Jr. Born at the beginning of Jack’s baseball career, Jack, Jr., was constantly compared-unfavorably-to his famous father and had trouble at school. As a soldier in Vietnam, he won a purple heart, but returned home addicted to drugs. In 1968, he was arrested on drug and weapons charges and was subsequently treated at a rehabilitation center. In 1971, shortly after leaving the center, he was killed in a car crash.

In 1968 and 1970, Jack, Sr., suffered heart attacks; he also began losing his sight because of a diabetic condition. On October 23, 1972, Rachel was cooking in the kitchen when she looked up and saw Jack, in the midst of a third heart attack, rushing toward her. “He put his arms around me, said I love you,’and dropped to the floor,” she remembers. At his death, Jack was 53.

For the next few weeks, Rachel was too grief-stricken even to see friends. “I wandered from room to room in my housecoat … I carried a picture of Jack wherever I was.”

The picture showed him sliding into home plate. “I could look at it and feel he was okay now,” she says. “He had made it home safely; nobody, nothing could hurt him anymore.”

Rachel didn’t stay idle for long. Within a month, she had decided to go back to work, knowing it would help her heal.

In 1973, she founded the Jackie Robinson Foundation, an organization dedicated to the nurturing and education of minority youth. “We give young people career counseling,” she noted, “and they all participate in give-back projects in their communities.”

Ninety percent graduate from college.

With the foundation securely on track, Rachel recently stepped down as chair to allow time for other activities-including spending time with her nine grandchildren. Her surviving children have thrived. Daughter Sharon, 46, is a practicing nurse-midwife and assistant clinical professor at the Yale School of Nursing: son David, 44, is in the import-export business in East Africa.

In writing her book, Rachel had to relive the pain as well as the accomplishments in her life. How would she counsel others faced with adversity? “If you can’t deal with something, rise above it,” she says. “If you still hit trouble, learn to fly.”